Each beach has its own unique fingerprint, made up of sand and stone, animals large and small, plants and algae. This, that I've labelled "moon snail beach" in my files, is a mostly sandy beach after the top few metres of stone and crabs; clean sand, on a gentle slope, and home to a forest of young bull kelp.

|

| Looking south. Salmon Point in the distance. |

The green stuff is eelgrass and sea lettuce. Reddish brown; sargassum, bull kelp, winged kelp. Red: eyelet algae, red noodles. Two moon snail collars visible here.

|

| Young kelp, under 2 metres long, holdfast to fronds. |

The holdfasts are not roots; they don't provide nutrients, at least for the kelp, but serve to anchor the algae on the sea floor, glued somehow to rocks. Even in strong tidal surges and wave action, the stipe is strong enough to resist breaking, as long as the holdfast is attached to something heavy and solid enough. Unfortunately for this youngster, it chose the wrong location, and a stone far too small to stay put under the waves. It will end up tossed and drying high on the beach.

Kelp needs to establish itself in the subtidal zone; young ones that grow intertidally don't survive, but they do provide habitat and food for small invertebrates while they last.

|

| Unwise choice of anchor stone. |

These foolish kelp youngsters all picked the same small stone. Even in calm water, they had no hope of staying anchored to the bottom.

|

| Winged kelp. This has been torn from its holdfast underwater. The holdfast will survive to grow another blade next year. |

While the blades of kelp only live about a month or two, holdfasts can live and grow for up to ten years or more! (Catalina Sea Camp)

|

| Red eyelet silk seaweed, covered in sand. This grows from the low intertidal zone downward. |

|

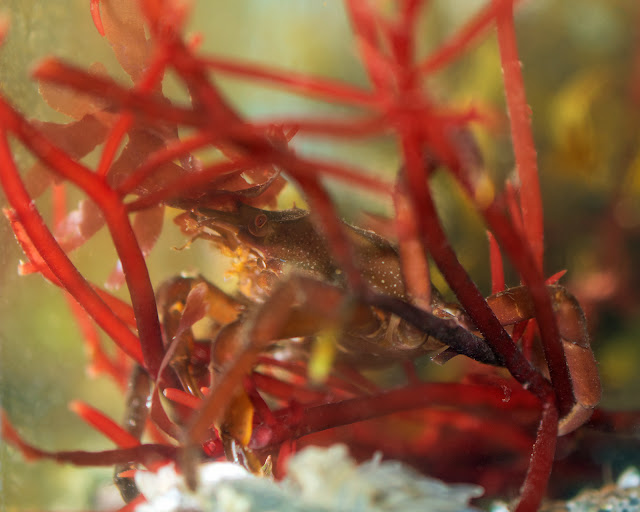

| A red noodle seaweed, attached to its holdfast. |

This one can live in the low intertidal zone, as long as it remains attached to the stone.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Cada playa tiene su propias características, incluyendo si se basa en piedra o arena, los animales grandes y pequeños que allí viven, las plantas y las algas. Esta playa, a la cual he nombrado "playa de caracoles luna" en mis archivos en la computadora, se compone principalmente de arena, aparte de los primeros metros de la zona superior, que está cubierta de piedras y cangrejos. La arena se inclina ligeramente hacia el mar; allí, en la parte más baja, crece un bosque de algas kelp juveniles.

Primera foto: la playa, mirando hacia el sur. En la distancia, Salmon Point.

Lo verde en la foto es hierba marina Zostera, y lechuga de mar. Lo café es sargazo y kelp. Y las algas rojas son el alga "ojete de seda", Sparlingia pertusa, y espagueti rojo. Se ven dos cuellos de caracol luna. también.

Segunda foto; un alga kelp juvenil, midiendo menos de 2 metros, desde el rizoide hasta las láminas.

Los rizoides no son raices; no proveen nutrición al alga, sino que sirven como ancla fijada de alguna manera a las piedras bajo el agua. Aun cuando la fuerza de la marea y las olas es vigorosa, las estipes (el tallo) son suficientemente fuertes como para resistir sin romperse, siempre y cuando el rizoide esté fijo en algo pesado y sólido. Mala suerte fue para esta kelp juvenil escoger una piedrita que no le puede detener en su lugar. Terminará aventada y secándose en las piedras al lado del mar.

El alga kelp necesita establecerse en la zona submareal para sobrevivir. Estos jóvenes no vivirán, pero mientras proveen habitat y comida para animalitos invertebrados.

Tercera foto: sitio mal escogido. Varias algas se fijaron a una sola piedrita. Ni en aguas tranquilas esto le iba a servir.

Cuarta foto: kelp "con alas", separado de su rizoide, que sigue en el agua y producirá nuevas láminas el año que entra.

¡Mientras las láminas de kelp viven solamente uno o dos meses, el rizoide puede vivir y crecer por diez años o más! (de Catalina Sea Camp)

Quinta foto: el alga "ojete de seda" cubierta de arena. Esta alga vive tanto en la zona baja intramareal como en la submareal.

Sexta foto: un alga "espagueti rojo". Esta puede vivir aquí en la zona baja intramareal mientras sigue en contacto con la piedra.