This is how Wikipedia describes them:

Meiofauna are small benthic invertebrates that live in both marine and fresh water environments. The term Meiofauna loosely defines a group of organisms by their size, larger than microfauna but smaller than macrofauna, rather than a taxonomic grouping. One environment for meiofauna is between grains of damp sand (see Mystacocarida).

In practice these are metazoan animals that can pass unharmed through a 0.5 – 1 mm mesh but will be retained by a 30 – 45 μm mesh, but the exact dimensions will vary from researcher to researcher. Whether an organism passes through a 1 mm mesh also depends upon whether it is alive or dead.

And I always have to look up micrometres (μm), too. Was that 100 times, or 1,000? A millimetre (mm) is 1000 micrometres (μm). So a member of the meiofauna is from 45 μm to 500 μm long. Quite a range.

With that out of the way, I Googled "meiofauna" and found a few - too few - pages. I'll have to continue the search, but already I'm fascinated.

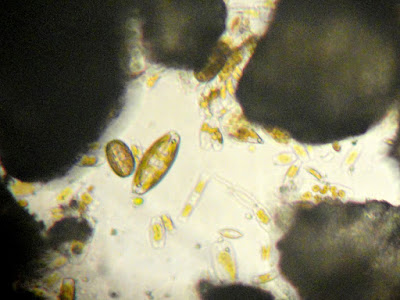

|

| Some of my meiofauna. Taken by removing the eyepiece from the phase microscope and pointing the camera down the tube. |

The marine meiofauna, defined as animals of microscopic size living in marine sediments, is one the earth’s richest and most diverse community extending from the shore to the deep sea. The marine meiofauna still contains numerous undescribed species and higher taxa. Special morphological adaptations evolved, especially in meiofauna living in the intertidal zone which is under a strong abiotic regime. Certain higher taxa evolved exclusively in the marine interstitial system. Evolutionary constraints caused elaborated life-cycles, migration patterns, special reproductive behaviours and structural adaptations. The interstitial system is also habitat for larvae and juveniles of certain macrofaunal species.

From Marbef.org (Marine Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning)

The majority of these organisms live in the top inch of the sand or mud. I sampled the top half inch. With Snail's help, I have more or less identified diatoms, (like those in the photo above, and more), ostracods (the jittery #8 from Sunday's post), hydroids, copepods, and worms. Hundreds of worms.

Most contaminants reside in sediments, and meiofauna are intimately associated with sediments over their entire life-cycle, thus they are increasingly being used as pollution sentinels. Because meiofauna have short lifecycles, the effects of a contaminant on the entire life-history can be assessed within a relatively short time. (Marbef)

Nematodes (worms) are relatively insensitive to man-made pollutants. I found in my samples several small, fat worms, a few polychaetes, identifiable by their red colour and their hysterical swimming style, and hundreds of long, sleek worms, from almost invisible at high magnification, to monsters a millimetre long or more.

|

| Mostly diatoms in various sizes and stages, probably a hydroid, and something making a chain. Taken with the low-power lens. |

|

| And while I was watching the diatoms, a worm snaked by, knocking away the sand grains in his path . This is his mid-section. At bottom left, one of the critters I was looking at. |

My grandson has come for his microscope, leaving me in its place a less powerful direct light one that the camera can't cope with. Back to the drawing board ...

|

| Stalked animals. I think the upper one is a hydroid. |

The diatoms next, probably tomorrow.

And nematodes seem to live forever (and multiply) in my garden. At least they don't seem to eat much. - Margy

ReplyDeleteIf you're going to be working with meiofauna, it helps a lot to stain them, since so much of it is transparent. Rose Bengal is what's normally suggested.

ReplyDeleteIt can also help to deoxygenate your sediment sample overnight (leave it in a covered container overnight) The more motile ones will migrate to the uppermost couple milimeters, and then scrape that with a spoon.

Margy; and what they eat, they poop, converted to plant food.

ReplyDeleteAnonymous; that's very helpful. I have, on occasion, left bowls of sand and water overnight, to observe the tiny tubeworms that set up camp in the top layer. I didn't think of covering the containers; I will do that in future.

I'll get myself some Rose Bengal. Thank you.

I might have been a bit ambitious with the suggestion of a good guide. There aren't too many easily available, but any good basic biology/zoology text will have some helpful info about the smaller critters (but not diatoms).

ReplyDeleteI forgot about rotifers. They attach to things by a short stalk and sweep foot into their mouths with cilia. Can sometimes be confused with hydroids. If you're lucky, you might also see gastrotrichs. (The only reason I even know about this obscure little group is that one of my friends was working on them at uni some decades ago. I was delighted to find an entire website dedicated to them.)

Oh, what a cruel grandson to introduce you to phase, then snatch it away again! But at least he didn't leave you completely bereft.

ReplyDeleteTo get the most out of your bright field scope, Molecular Expressions is a great starting point. They have some nice interactive simulations for how to do the adjustments for various kinds of microscopy

http://micro.magnet.fsu.edu/primer/index.html

Another great resource is Microscopy UK. The site is mess, but the content is worth it. They have a monthly online magazine, and the archives are chock full of articles about technique, critters, scopes and scope history, and more.

http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/mag/indexmag.html

If it's at all possible on your scope, try to set it up for 'dark field' illumination. it's not quite so nice as phase, but it's much better for live critters than bright field. For general hunting, no special slide prep is needed--just stick a well slide in and gawk. To slow down fast critters, you can add methyl cellulose to increase the viscosity.

Two books worth having:

"Guide to Microlife" by Kenneth G Rainis. Still in print, but expensive for a smallish book (US$50), and not easy to find used. But it's a wonderful field guide to the meiofauna. It's written for kids, but is just as useful for adults. Lots of good photos.

Eric V. Grave "Using the Microscope - A Guide for Naturalists"

Out of print and hard to find but it's excellent.

Have fun with the new toy, and I'm looking forward to lots of pictures!

Ceratina

Hi, Ceratina.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the tips! I've spent hours today browsing through the Microscopy primer, and then trying to translate some of what I learned to Element. I fixed one old microscope photo, and ruined another. Progress, of a sort.